Introduction

If you’ve ever heard a strange “peent” echoing across a damp meadow at dusk, you may have been in the company of one of North America’s most unusual birds: the American Woodcock. This plump, short-billed shorebird doesn’t live by the ocean like most of its relatives but instead occupies the brushy fields and young forests of eastern North America. Birdwatchers often compare the woodcock to a feathered oddball, with its big eyes set high on its head and its spiraling courtship flights that light up spring evenings. Knowing how to identify, listen for, and understand this bird not only sharpens your field skills but also connects you to a natural spectacle that many never notice, even while it plays out right under their noses.

What Is the Scientific Name of the American Woodcock?

The American Woodcock carries the formal scientific name Scolopax minor, placing it within the larger Scolopacidae family that also includes sandpipers and snipes. Imagine it as the woodland cousin of those beach-walking shorebirds, trading sandy flats for damp forest floors. While its relatives probe tidepools, the woodcock relies on a bill designed for earthworms, the staple of its diet. That long, flexible bill tip can sense movement underground, a tool as specialized as a metal detector at the beach.

It is very similar to the Wilson’s Snipe, another member of the same family. Both birds have stocky bodies and probing bills, but the woodcock’s head looks almost cartoonish, with eyes so far back that it can watch for predators from nearly every angle. In the field, that eye placement matters: spotting just a round, dark eye peeking from leaf litter is often your first clue.

By knowing the woodcock’s place among the shorebirds, birders can better anticipate its behavior. Unlike many ground-nesting songbirds, it doesn’t rely on camouflage alone; it has the probing lifestyle and twilight courtship inherited from its sandpiper kin. (Fun side note: it is sometimes referred to as a timberdoodle, mudbat, or bogsucker.)

So next time someone asks why this bird looks so different from a sparrow or a thrush, you can point back to its family tree. It’s a shorebird in disguise, adapted to forest floors instead of open beaches.

Where Does the American Woodcock Live?

If you want to find an American Woodcock, skip the coastline and look inland. This bird thrives in damp, brushy woodlands, old fields, and thickets where earthworms are plentiful. It’s a classic example of “early successional habitat,” the type of young forest that springs up after logging or fire. It’s a bird that needs messy, shrubby corners rather than neat, mature woods.

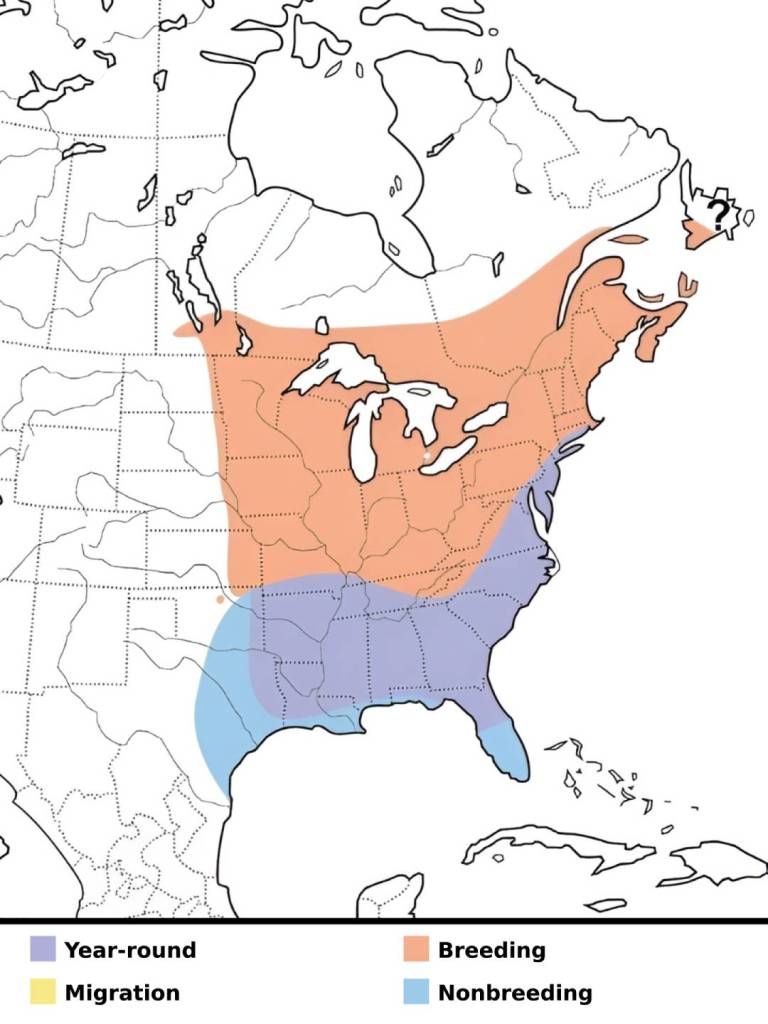

Its range stretches broadly across eastern North America, from the Great Lakes and New England down into the South. In summer, woodcock nest as far north as southern Canada, but come winter they shift to states in the U.S. with milder climates, such as Louisiana, Arkansas, and the Carolinas. Migration happens quietly at night, often going unnoticed, unlike the noisy flocks of migrating geese overhead.

A field tip is to walk the edges of overgrown fields at dusk in March or April. You might flush a woodcock from the ground with a flapping of wings, or hear that telltale “peent” from a bare patch of ground. Because they are ground dwellers, they also need open spots for their display flights, which is why old farm fields or meadows near woods are prime territory.

The American Woodcock is a priority bird. This status not only highlights that its long-term survival is threatened, but it also means conservation efforts geared toward helping this bird will also help other species that rely on the same habitats. The woodcock’s numbers decline when brushy habitat is lost to development or allowed to grow into tall forest. Spotting one can be a sign of healthy young woodland. By knowing where this bird chooses to live, we understand how important it is to keep those transitional spaces.

What Does the American Woodcock Sound Like?

One of the surest ways to detect a woodcock is with your ears. Their signature call is the nasal “peent” given at ground level, often compared to the sound of a buzzy toy horn. Some birders jokingly say it sounds like a frog with allergies. Whatever you call it, once you’ve heard it, you won’t mistake it for anything else.

During courtship, the male adds another layer: a twittering sound created not by his voice but by air rushing through his wing feathers as he spirals upward into the evening sky. That wing whistle blends with a liquid “chirp” vocalization as he zigzags back down, making his performance a full sensory show.

In comparison, a Wilson’s Snipe has its “winnowing” display, but that comes across more like a ghostly humming. The woodcock’s sounds are sharper and more comical, matching its chunky appearance. If you’re trying to identify it in the field, remember this: the peent comes first on the ground, then the twittering wings and chirps during the flight. Listen for the pattern rather than just the single sound.

Without tuning in and knowing what to listen for, you can easily walk right by. The woodcock’s earth-toned camouflage hides it completely during the day. It’s the voice that reveals its presence. Birders who learn to recognize these sounds unlock encounters that others miss. (Another fun fact: those wing whistles aren’t just for show; the unique feather structure is so specialized that if a feather is missing, the whole performance sounds off.)

The American Woodcock’s Dance Explained

Few natural events compare to the American Woodcock’s “sky dance.” At dusk in early spring, males begin with a series of “peents” on the ground, then suddenly launch into a spiraling flight high into the sky. As they rise, the air through their wing feathers creates a musical twitter, and once at the peak, they descend in a zigzag pattern, giving soft chirps all the way down.

Think of it as a mix between a fireworks show and a choreographed aerial display. Where a grouse may thump its wings or a meadowlark may sing from a perch, the woodcock takes the stage in the open sky, using both voice and wing sounds. Catching this spectacle shows how a bird can turn physics into art.

To catch this performance, timing is key. Arrive at an open meadow bordered by woods just as the light fades in March or April. Stand quietly and wait. If you hear that first peent, you might be about to see the show. Move slowly, because males often return to the same small spot after each flight.

The sky dance is crucial for the species. Females choose mates based on these displays, so the success of each male’s performance shapes the next generation. When you take that into consideration, every spiral feels more than entertainment; it’s survival on display. (Also, if you’re patient, you can often predict exactly where the bird will land. Like watching a performer hit their mark on stage.)

American Woodcock in New York and the Northeast

The Northeast, especially states like New York, provides a prime environment for the American Woodcock’s spring displays. In upstate fields, brushy wetlands, and abandoned farmlands, birders gather at dusk to witness the sky dance. For many, hearing the first peent of the year signals that spring migration has arrived.

In New York, the American Woodcock is most often spotted in low, damp areas with plenty of young forest growth, such as the transitional space between open hayfields and regenerating clearcuts. The former may be too exposed, while the latter gives that perfect mix of open ground and shrubby cover. Birders often mark calendar dates to revisit the same meadows year after year, knowing males will perform in the same locations year after year.

While the woodcock’s spring flights grab the spotlight, the Northeast also serves as an important stopover during migration. Birds moving through upstate New York rely on a patchwork of moist fields, regenerating forests, and shrubby wetlands to refuel on earthworms before pressing farther north. Because these habitats are scattered, a single abandoned farm field or clearcut can hold surprising numbers of these birds in early spring. Unlike the sky dance, these stopover sites are easy to overlook. You might just notice small probing holes in soft soil, or a bird lifting off from the ground at close range when you walk through.

Because these sites can hold many individuals in a small area, surveys in the Northeast often record spikes in numbers during migration weeks. That’s one reason woodcock counts vary so much from season to season. For birders, it means you might find a quiet field empty one evening and alive with activity the next. Paying attention to soil conditions and recent weather can help, wet ground after a rain is more likely to draw them in.

American Woodcock Eggs, Size, and Predators

Despite the dramatic spring display, the American Woodcock nests quietly. The female makes a shallow scrape on the ground and lines it with leaves. A typical clutch is four mottled eggs that blend well with the surrounding leaf litter. The eggs are fairly large compared to most songbirds, typically measuring 1.4 to 1.7 inches in length.

The female is about 10 to 12 inches long, stocky in build, and slightly smaller than a pigeon. She incubates alone, relying on her brown plumage to remain hidden while on the nest. If disturbed, she usually flies off suddenly, often before the nest is even noticed.

Common predators include raccoons, foxes, skunks, and snakes. Eggs and chicks are particularly vulnerable, so the bird’s best defense is remaining still and blending into the background. This is effective until a predator or person happens to come near.

If you flush a woodcock in spring and it lands only a short distance away, you may have walked near a nest. It’s best to keep moving and avoid the area so you don’t increase the risk of a predator finding it.

Ground-nesting birds like the woodcock depend on good quality habitat to maintain survival rates. Knowing these risks helps explain why protecting young forests and brushy cover is an important conservation priority.

Conclusion

The American Woodcock shows a lot of contrasts. It belongs to the shorebird family but lives in forests, has a short, rounded body yet performs an elaborate aerial display, and nests quietly on the ground while being most noticeable during its loud spring courtship. For birdwatchers, learning its calls, habitats, and behaviors adds another layer of understanding to the landscape. Each sound, flight, and nesting attempt ties into the seasonal cycle of migration and renewal. By noting where these birds live and how they manage to survive, we also see the importance of young forests and brushy fields that support many other species. When evening comes and you hear that nasal “peent,” you’re hearing a reliable marker of spring on the land.

Leave a comment